The GM's Dagger Pt 1

Knowing your role

For awhile, I’ve been struggling to figure out what exactly to write about. Have I said everything that needs to be said? What can I still contribute to the discussion of RPGs? Sometimes, it definitely feels that way, especially these days. I’ve been a little burnt on RPG discourse, but then I sat down with Dave from Tooky’s Mag and had a post on X go thermonuclear in response to WotC’s latest campaign for sodomy and perversion. In my interview with Dave, we discussed a lot of the deep lore and history of the online RPG sphere, namely the contributions of the BrOSR, and it became plainly obvious that all of this was a little impenetrable. I've known for awhile that Wizards of the Coast was losing its grip on the industry. The fact that they would post a piece of art so hideous to pander once again to the alphabet coalition shows how creatively and morally bankrupt the enterprise has become and the fact that an account of my size can ratio them into oblivion (literally double their likes) shows that people are tied of it all. They want something new, but WotC still has the clearest path for the onboarding of new players. Dave and I discussed parallelism during our show and clearly that's the route we need to take. Parallelism takes time and effort though. You can't just build a WotC competitor overnight even if we need one right now. We can't despair our situation though. We need to start somewhere. A year or so ago I had an idea for a pamphlet called “The GM’s Dagger.” It's meant to be a pocket guide for GMs. A kind of side arm to carry at all times. Every knight carried a dagger and so should every GM. That's what this is. I’ll be publishing a series of articles designed to introduce new players to these ideas over the next few weeks. Eventually, I'll compile them into two books, one for players and one for GMs. This article will comprise the first entry of the GM’s Dagger which will define the roll of the Game Master. I encourage all of you to share this and all subsequent articles with inquiring players and first time GMs. We’re going to build an alternative infrastructure for onboarding new players one brick at a time. Here’s the first brick.

1. Knowing Your Role

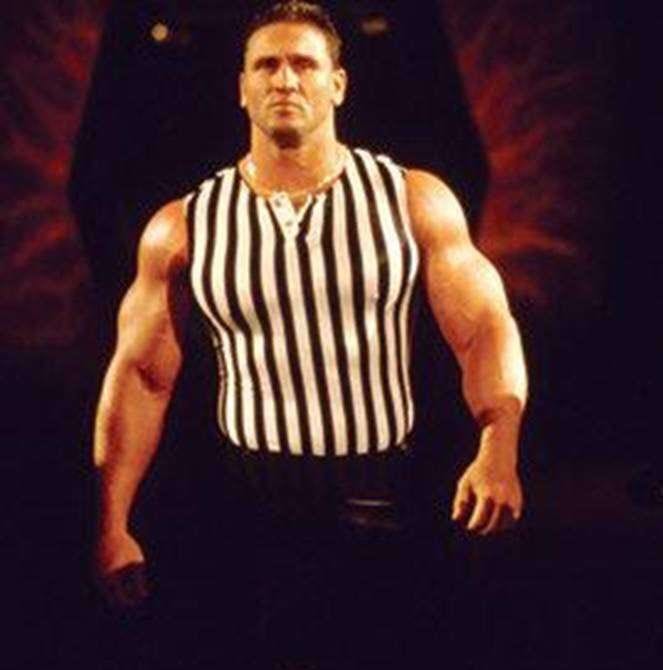

In discussions of RPGs, one will hear a lot of talk about the illusive and put-upon figure known as “The GM.” There are endless memes and stories that portray the GM as some kind of cross between an evil mastermind and a frustrated parent of toddlers. Most people who enter the hobby these days are first exposed to the game and its various roles through internet gaming culture. Their preconceptions are an amalgamation of memes and YouTube videos which propagate disinformation. The Game Master, or GM for short, is not Ra’s al Ghul plotting to overthrow world governments. He is not a frustrated parent of unruly children. He is not a “world-weaver” or “story-crafter” or any other pretentious self-bestowed title found in someone’s Bluesky bio. Rather, the role of the GM is that of a referee. The Game Master possesses a deep understanding of the rules of the game, enforces outcomes on the players based on the rules, and arbitrates between players when disputes arise.

I understand why many first-timers believe that there's an authorial aspect to being the Game Master. When observing the game from the outside, one will see that a single player generally sits at the head of the table. He does the bulk of the talking and seemingly every action is approved or disapproved by him. There are all of these maps and environments that aren’t present there at the table and seem to be spontaneously generated from the mind of this shot-caller figure. As if that weren’t enough, this so-called “Game Master” is usually giving voice to hundreds of different characters that the other players are interacting with. In martial arts, there are legends of how certain fighting styles were developed by fishermen who watched Shaolin monks practice their forms from a distance and adapted their styles from what they could see. I believe a similar phenomenon has occurred in the development of RPGs. The first generation of players were college-educated young men. They were used to complicated wargames and engaged with this new style of game the way they did with other games; the read the rules and ran the game as outlined. The second generation started playing much younger than the first though, usually between the ages of nine and thirteen based on anecdotal evidence, and as a result did not comprehend the rules which were written and laid out in a very dry fashion. They learned by observation first and that built the foundation for their game. Some of them did eventually go back, read the rules and adapt but many didn’t. Their foundation for gaming was not Dungeons & Dragons as-written, but a folk game loosely adapted from the original.

In the 2019 documentary The Secrets of Blackmoor which covers Dave Arneson’s history with wargaming and how he contributed to the original Dungeons & Dragons, the subjects of the documentary tell stories about how they would roleplay to add context to the results of their roles. Did an army pass a morale check that they absolutely shouldn’t have? There was an enthusiastic officer who refused to let his men surrender. It was a natural evolution of nerdy guys playing games. It was not the sum total of the experience. That context was lost on 9 year-old Timmy when he watched his college-age brother running the game with his friends. He heard his brother doing funny voices and heard his stories about the epic adventures his party went on after the fact but he wasn’t aware that he was seeing the sizzle, not the steak. This problem has only gotten worse as time goes on, especially as game companies have leaned into this notion. Almost every rulebook you buy now has some variation of “If you don’t like a rule, don’t use it” or “It’s about having fun,” printed before the actual meat of the rules. The problem with this is, well, it doesn’t work very well. Narrative-first gameplay requires GMs to craft some kind of story that’s closed enough to create a curated experience but open enough to make players feel like they actually matter. They have to worry about progression, pacing, and keeping player interest. All of these things are incredibly stressful and above-and-beyond the call of duty for a GM. They require extensive prep and dedication and they make gaming a massive time-sink. This is a tough sell for busy people, brining us back to the actual role of the GM. He should know the rules, enforce them at the table and arbitrate when disputes arise.

The GM is the judge, the referee and the rulekeeper. He has no other duties aside from this, not even hosting. It doesn’t require acting talent or the creativity of a literary master. It does require reading-comprehension, selflessness and consistency though. A GM must be detail-oriented, firm and fair. In subsequent chapters, I will explain the concepts that will help you achieve these lofty goals. Being a Game Master is not easy, but it is far simpler than internet RPG culture portrays it as being. If I can leave you with one piece of advice that I’ll expand upon in the next chapter, it is this; the rules matter above all else and it is your job to make sure that they are adhered to and interpreted.